Bee Blog - August 2020

Last year I decided that I would attempt to breed my own queens. Having a few spare queens is quite useful to the beekeeper. Old queens can be replaced in hives that are not performing well at a time of the beekeepers choosing to keep colonies strong.

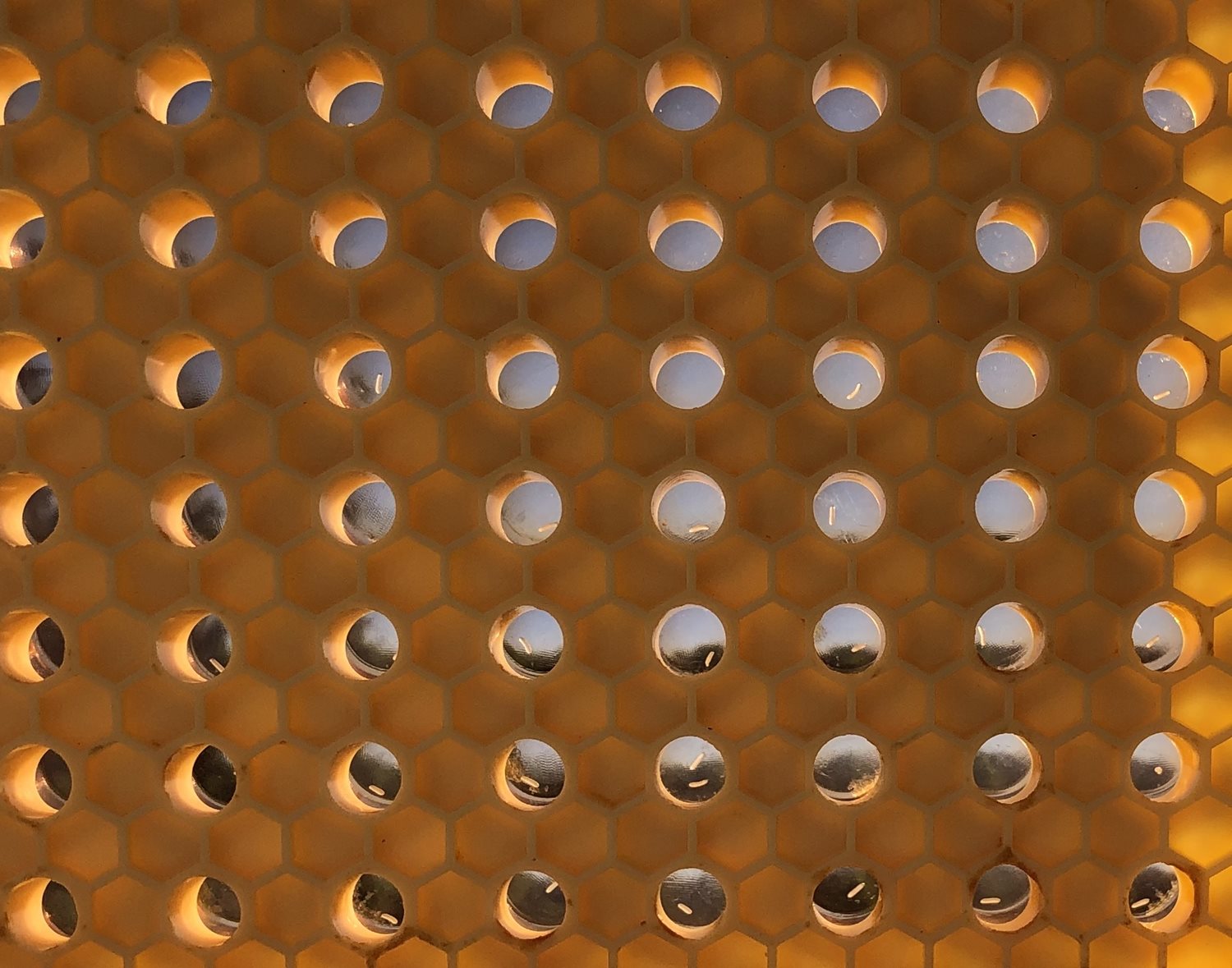

My plans did not work out last year. The start of the process for the method of producing queens I had chosen involved harvesting eggs from an existing queen in one of my hives. A plastic box which mimics the bees natural honeycomb with individual cells the same size and spacing as the natural cells is placed into the hive and the queen is enclosed into this plastic box in which the cell spaces have a removable cap on the reverse side. These caps are removed when the queen has deposited an egg in each individual caps.

Last year I was on the verge of starting the process when the colony I had chosen decided to swarm taking my donor queen with them. Had I been one day earlier I would have boxed the queen, I could have harvested her eggs and in the process I would have stopped the swarm as the queen could not leave the hive. As I have learned to my cost several times now, the bees are not always obliging or perhaps they just have a wicked sense of humour, regardless, last year I had to cancel my plans.

This year I tried again. The method I had chosen involved harvesting the queens eggs that were no more than three days old and placing them in a queen less colony in a certain way so as to encourage the bees to draw out and construct queen cells.

This year I managed to catch the queen that I wanted to breed from and place her in my egg harvesting box. Three days later I returned checked that eggs were present and released her from the box back to her colony. My photograph this month shows a close up picture of the individual cells with a translucent cap on the back of the cells backlit to show the individual eggs. The eggs are the shape of a grain of rice but only about a tenth of the size. My chosen queen had performed well with an egg in almost every cell.

I removed the individual caps, each containing an egg and hung them on a receptacle from a bar attached to an empty super frame and placed this frame in a hive where I had already removed their queen. The bees soon realise they are queen less and look around for eggs that are less than three days old so that they can make a new queen. They soon find the eggs that have been placed on the frame hanging down vertically in cups which mimic the beginning of queen cells. Following their natural instinct the bees start forming wax extrusions around the plastic cups and start tending to the eggs and larva when the eggs have hatched, feeding them a strong diet of royal jelly. The larva develop rapidly and after about 8 days they are fully formed and the bees seal the new queen cell. The bees then incubate these queen cells for about a further 8 days when the new queens will emerge from their cells.

Not all of the eggs that are placed in the queen less hives will be successfully turned into queens for various reasons. I had placed 20 cups containing eggs into the queen less hive and probably because of my inexperience my success rate was low but I was very pleased to have been successful in producing 3 new queens.

There can only be one queen in the hive and what generally tends to happen is that the first new queen to emerge from her cell quickly locates any other queen cells in the hive and kills the developing larvae before it emerges. Obviously when trying to breed several new queens the beekeeper does not want this to happen. After the bees have sealed the developing queen cell therefore the beekeeper places a plastic cage, commonly known as a “hair roller”, as that is what it looks like, over the cell so that when the new queen emerges she is contained within this cage and cannot kill off her sisters. The beekeeper can then harvest each newly emerged queen and move her on to the next process ; being mated.